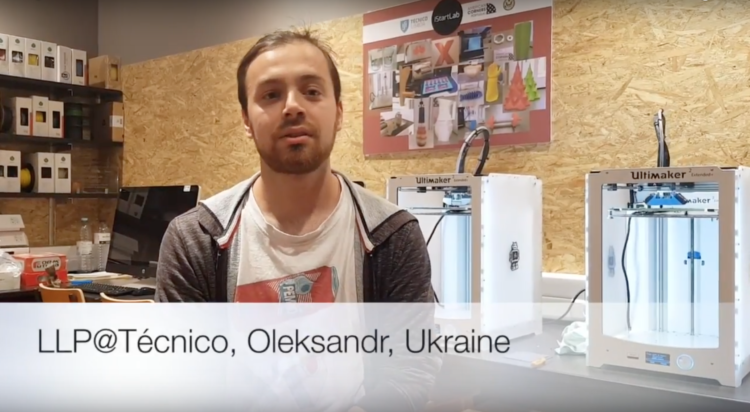

[:en]One of my last week’s tasks was to edit videos with testimonials from students of this semester’s edition of the LLP@Técnico program. Lean LaunchPad is an entrepreneurial teaching method created by Steve Blank, that I have adapted to the needs of Técnico, after taking a course with its author in 2013. In this program, offered as an option for students of various academic programs, we try that participants experience the challenges facing the founders of startups. Having been absent from the country, I asked Diogo Henriques, who works with me in this program since the beginning, to record some testimonials by the participants. One of the testimonies that surprised me the most, was by Oleksandr that highlighted the way the program was structured, knowing exactly what he had to do each week. You need to understand that, for a student of engineering, an experiential program in entrepreneurship is extremely uncomfortable when compared to the traditional courses in engineering: no problem statement, no data, and is not known whether there is a solution. Each group of students has to develop their own project and it radically changes almost every week since they have to validate their hypotheses by conducting a minimum of 10 interviews per week and present the results to their colleagues in class. The program lasts for 11 weeks and teams often find their final project well after the sixth week of classes. This is precisely one of the most valuable lessons: the validation of a business opportunity requires hard work.

How do we do the structuring that Oleksandr highlighted? The best analogy I can find for the model we use in LLP @ Technician is the Lego blocks. When I was given my first set of basic parts I could do almost everything but in a very stylized way, the roofs looked like stairs and the cars had no wheels. Later I was given tiles, wheels, doors and other parts that allowed me to create more detailed models. However, I could use the blocks at my disposal at each moment to build anything I wanted. Similarly, LLP@Técnico program uses Alex Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas (BMC) blocks to provide students with the tools to develop the business model of their own projects. The nine blocks that divide the program are:

Opportunity assessment. In the first two weeks, we bring together some methods for idea generation with the identification of the market size and type for an initial filtering of ideas.

Value proposition. In the case of an engineering school, it is usual that students master a favorite technology that they want to use in their project, so the second week is dedicated to the identification of problems that they can solve with it. They need to validate that the problem exists and what is its value.

Customer segments. In the fourth week, we introduce the need for selecting the initial customer segments. They must gain empathy with the customer’s tasks, pains, and gains.

Channels. After knowing who their customers are, the next week is dedicated to the identification of how they want to buy the product and the costs associated with the channel, whether physical or virtual.

Customer relationships. The sixth week is dedicated to customer acquisition costs and the customer lifetime value.

Revenue model. In the following week, students learn the strategies of the various revenue models and tactics for the pricing model. It is here that students validate the potential of their project to generate revenue.

Partners. In the eighth week, we move to the left side of BMC starting by identifying their potential partners, the reason why they need them, and their willingness to join the project.

Resources, activities, and costs. The ninth week is dedicated to the hardest part of the project, which is the validation of the resources and activities necessary to create the value proposition, as well as the evolution of its costs. The main objective is to identify the investment needed in the different stages of the project.

Lessons Learned. The last two weeks are used to teach students to present their final project (see my post on “5 ideas for memorable presentations“).

The challenge to students is to integrate these concepts into their project even if, at any time, they may need to restart it from scratch. If they decide to make a new construction, they know how to use the blocks they already have worked with. This permanent need for restarting is the reason why I have a slide in the fifth week of classes showing the “LLP roller coaster”. I say to students that their happiness quotient should be at the lowest level, but it will certainly rise. The video with Adam’s testimony highlighted this and he confirmed that it is so. You can learn more about the program LLP@Técnico and see the testimonies of these students at the site: istartlab.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/learn/llp-tecnico.

Luís Caldas de Oliveira, @LuisCaldasO

Adapted from my article in Jornal i, May 22rd, 2018[:pt]Uma das minhas tarefas da passada semana foi editar vídeos com testemunhos dos alunos da edição deste semestre do programa LLP@Técnico. O Lean LaunchPad é uma metodologia de ensino de empreendedorismo criada por Steve Blank, que adaptei às necessidades do Técnico depois de um curso que fiz em 2013 com o seu autor. Neste programa, oferecido como opção a alunos de vários cursos, procuramos que os participantes experienciem os desafios que enfrentam os fundadores de startups. Por ter estado ausente do país, pedi ao Diogo Henriques, que trabalha comigo neste programa desde o início, para gravar alguns testemunhos dos participantes. Um dos testemunhos que mais me surpreendeu, foi o do Oleksandr que destacou a forma como o programa estava estruturado, sabendo exatamente o que tinha de fazer em cada semana. É preciso explicar que, para um aluno de engenharia, um programa experiencial de empreendedorismo é extremamente desconfortável quando comparado com as disciplinas tradicionais: não há enunciados, não há dados e não se sabe se há solução. Cada grupo de alunos tem de desenvolver um projeto próprio que muda radicalmente quase todas as semanas, pois devem validar as suas hipóteses com um mínimo de 10 entrevistas por semana e apresentar os resultados aos seus colegas na aula seguinte. O programa tem a duração de 11 semanas e é frequente haver grupos que só encontram o projeto final bem depois da sexta semana de aulas. Esta é precisamente uma das lições mais valiosas: validar uma oportunidade de negócio exige muito trabalho.

Como fazer então a estruturação que o Oleksandr destacou? A melhor analogia que consigo encontrar para o modelo que usamos no LLP@Técnico é o dos blocos de Lego. Quando me ofereceram o primeiro conjunto de peças básicas eu conseguia fazer quase tudo mas de forma muito estilizada, os telhados pareciam escadas e os carros não tinham rodas. Mais tarde ofereceram-me telhas, rodas, portas e outras peças que me permitiam fazer os modelos com maior detalhe. No entanto, em cada momento as peças ao meu dispor podiam ser usadas para fazer qualquer construção que eu quisesse. De igual forma o programa LLP@Técnico usa os blocos do Business Model Canvas (BMC) de Alex Osterwalder para ir oferecendo aos alunos ferramentas de desenvolvimento do modelo de negócio dos seus projetos. Os nove blocos em que dividimos o programa são:

Avaliação de oportunidades. Nas duas primeiras semanas, juntamos algumas metodologias de geração de ideias com a identificação da dimensão e o tipo de mercado para uma filtragem inicial das ideias.

Proposta de valor. Tratando-se de uma escola de engenharia, é habitual os alunos terem uma tecnologia favorita que querem usar no seu projeto, pelo que a segunda semana é dedicada à identificação dos problemas que podem resolver. É preciso validar que o problema existe e qual é o seu valor.

Segmentos de clientes. Na quarta semana introduz-se a necessidade de seleção dos segmentos de clientes iniciais. É preciso ganhar empatia com as suas tarefas, as suas dores e os ganhos que podem obter.

Canais. Conhecendo os clientes, a semana seguinte é dedicada à identificação da forma como eles desejam comprar o produto e os custos associados ao canal, seja físico ou virtual.

Relação com clientes. A sexta semana é dedicada aos custos de aquisição de clientes e ao valor que poderá trazer.

Modelo de receita. Na semana seguinte os alunos aprendem as estratégias dos diversos modelos de receitas e as táticas para o modelo de preços. É aqui que os alunos validam o potencial do seu projeto para gerar receitas.

Parceiros. Na oitava semana passamos para o lado esquerdo do BMC começando por identificar os parceiros, a razão da sua necessidade e a disponibilidade para se associarem ao projeto.

Recursos, atividades e custos. A nona semana é dedicada à parte mais difícil do projeto, que é a validação dos recursos e das atividades necessárias para a criação da proposta de valor, bem como a evolução dos seus custos. O objetivo principal é identificar as necessidades de capital em função das etapas de desenvolvimento do projeto.

Lições Aprendidas. As duas últimas semanas são usadas para ensinar os alunos a apresentar o projeto final (ver a minha crónica “5 ideias para apresentações memoráveis”).

O desafio colocado aos alunos é de irem integrando estes conceitos no seu projeto mesmo que em qualquer momento haja a necessidade de começar tudo de novo. Se decidirem fazer uma nova construção já sabem como usar os blocos com que já trabalharam. É este permanente recomeço que está na origem do sucesso de um gráfico, que apresento na quinta semana de aulas sobre a “montanha russa LLP”. Indico aos alunos que devem estar no nível mínimo do seu coeficiente de felicidade, mas que este irá certamente subir. O vídeo com o testemunho do Adam que destacou esse momento confirma que assim é. Poderá saber mais sobre o programa LLP@Tecnico e ver os testemunhos destes alunos no site istartlab.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/learn/llp-tecnico.

Luís Caldas de Oliveira, @LuisCaldasO